The learner as corpus designer

Guy Aston

Advanced School for Interpreters and

Translators, University of Bologna

1. Introduction

In recent years it has been

suggested that it may be both useful and motivating for teachers and learners

to construct their own corpora to analyse with appropriate interrogation

software. Such suggestions include the construction of:

·

collections

of texts written by learners themselves (Seidlhofer 2000), or which have been

previously read by them during their courses (Gavioli 1997, Willis 1998);

·

collections

of texts which illustrate a particular text-type and/or domain of use (Bowker

1998; Maia 2000a, b; Pearson 1998, 2000), or which illustrate particular

linguistic features (Bertaccini & Aston 2001; Varantola 2000).

Proposals of the first type see

‘home-made’ corpora as a means to cast further light on previously encountered

texts and linguistic features, where analysis is facilitated by virtue of the

learners’ prior familiarity with the texts involved. Proposals of the second

type instead see them as a means to investigate unfamiliar features, domains or

text-types which are inadequately documented by existing resources –

particularly in the area of translator training, where the ability to construct

specialized corpora is increasingly seen as fundamental for the identification

of domain-specific terminology (Pearson 1998, 2000; Maia 2000b).

The main ideas

underlying these proposals appear to be that:

·

‘home-made’

corpora may be more appropriate for learning purposes than pre-compiled ones,

insofar as they can be specifically targeted to the learner’s knowledge and

concerns;

·

such

corpora permit analyses which would not otherwise be readily feasible,

providing a specialized hypertextual environment for the study of particular

texts and instances;

·

by

compiling corpora for themselves, learners may gain insight into how to select

and use corpora appropriately, acquiring skills and knowledge which may be of

value to them in the future.

Against these potential

benefits, however, we must balance the costs of corpus construction. A

considerable amount of work is likely to be involved, and in comparison with

corpora constructed by professional researchers, the quality of the product is

likely to be relatively low. Home-made corpora will typically be more

opportunistic, less carefully designed and edited, and less comprehensively

encoded and annotated than those compiled by experts. Consequently, teachers

and learners may be unconvinced that it is worth building corpora of their own.

In this paper I shall outline an intermediate strategy which, I argue, can

provide some of the same benefits while considerably reducing these costs, by

providing specialized environments for particular areas of study, while at the

same time offering insights into how to design, select and use corpora

appropriately.

2.

Corpora in language learning

In both corpus linguistics and

language pedagogy it is a well-established principle that design must be based

on an analysis of users’ objectives. From this perspective, there are at least

five types of corpus-based activity that appear relevant to language learners

(Aston 2000, 2001b):

·

form-focused

activity, aiming to establish and practice the use of particular linguistic

features (“data-driven learning”: Johns 1991);

·

meaning-focused

activity, aiming either to establish meanings in a particular corpus text or to

understand the concepts referred to and the functions realized in a particular

text-type – what we might term ‘data-driven cultural learning’;

·

skill-focused

activity, aiming to develop particular reading skills and strategies,

particularly of a ‘bottom-up’ variety (Brodine 2001);

·

reference

activity, where corpora are used for support in tasks involving other texts, in

particular as aids to reading, writing and translating (e.g. Owen 1996;

Zanettin 2001 amongst many others);

·

browsing

activity, where learners alternate between the previous types of activity in

serendipitous explorations of the corpus (Bernardini 2000a, b).

Home-made corpora can

lend themselves to all these uses. We may briefly exemplify them in relation to

a learner-designed corpus of astrophysics research articles (Raffa 2000). From

a form-focused perspective, this corpus is an excellent resource for

identifying astrophysical terminology and establishing its uses. From a

meaning-focused one, it provides many opportunities to learn about white

dwarfs, black holes, red giants, etc., as well as about the general methodology

of astrophysical research. From a reading skills perspective, it can provide

focused practice in such areas as the parsing of complex nominal groups, or the

resolution of anaphoric and cataphoric reference in this kind of text. And

obviously, it can serve as a reference tool while reading, writing or

translating astrophysics research articles (the corpus was originally designed

to provide a resource for non-native speakers engaged in astrophysical

research), since it provides an intertextual background against which to

construct and evaluate interpretative or productive hypotheses. Last but not

least, it is a corpus that can be browsed serendipitously, travelling from one

linguistic or cataclysmic variable to another.

All

these types of activity, it should be stressed, lend themselves to being

contextualized in a framework of communication, since they provide numerous

opportunities for report and discussion of linguistic, social, cognitive and

methodological issues. Thereby they allow not only extensive communicative

practice, but can also develop linguistic awareness and encourage learning

autonomy (Aston 2000, 2001b).

2.1 Why

make your own corpora?

Why, however, should learners bother

to construct their own corpora in order to engage in activities of these kinds?

To use an analogy, making your own corpus seems rather like making your own

fruit salad. Why make your own when you can buy a tin off the supermarket

shelf? The reasons (for both corpora and fruit salads) appear similar:

·

Control.

You can devise your

own recipe, choosing your own ingredients, thereby obtaining assortments that

may be unavailable in pre-packaged versions. There was no publicly-available

corpus of astrophysics research articles which could be used to investigate the

particular linguistic and conceptual characteristics of the latter. The BNC,

for instance, contains only 10 written texts which mention astrophysical white

dwarfs – too small and hetergoeneous a sample to warrant generalizations in

this domain.

·

Certainty.

If you make your

own fruit salad, you have a good idea of what went into it, and this makes it

easier to decide what that strange-looking bit was, or why it tastes too bitter

or too sweet. It is much easier to interpret concordances or numerical data if

you know exactly what texts a corpus consists of, since this allows a greater

degree of top-down processing. It takes some time to gain sufficient

familiarity with a pre-packaged corpus to recognize particular texts, or to

interpret results in the light of its particular quirks. With one you have made

yourself it is easier to make adjustments, and to recognize the limits to

inferences.

·

Creativity.

Corpus-making, like

cooking, can be fun, giving scope for individual panache. It is also gratifying

when your fruit salad turns out to be delicious, or your corpus a useful

resource.

·

Critical

awareness. Through

trial and error, and consulting books and experts, you will probably become a

better chef (whether of corpora or fruit salads) as you compare the effects of

different proportions of different ingredients, or discover that mixing popular

science with research articles is not always a good idea. Even if you are

unsatisfied with the results of your efforts, the experience of making your own

seems likely to make you a more critical corpus user, increasing awareness of

how design affects the results – results which are (to quote Sinclair 1991: 13)

“only as good as the corpus”.

·

Communication.

Making your own

corpus or fruit salad can have more social spin-offs than opening a supermarket

tin, providing lots to talk about with co-constructors and with other chefs, as

well as with the consumers of the end product. Making your own opens up a whole

range of opportunities for learners to discuss how best to compile and encode

corpora for particular purposes, and to discuss how good they effectively are

for these purposes and how they might be improved.

2.2 Why

use standard pre-packaged corpora?

Since there is a market for tinned

fruit salad, there must presumably be some arguments in its favour.

Pre-packaged corpora typically offer advantages compared with the home-made

variety in terms of:

·

Reliability.

A pre-packaged

corpus (provided it is well-designed and fits your needs) is likely to give

more reliable results. Just as tinned fruit salads are subject to quality

controls based on market research, it is more likely that a pre-packaged corpus

will be reasonably “representative” of the population it aims to cover (Biber

1993), and carefully “balanced” amongst the different types of text which make

up that population.

·

Documentation.

Pre-packaged

corpora generally provide better documentation than home-made ones. With an

off-the-shelf fruit salad, it is easier to find out the exact sugar content,

and exactly how many calories you are consuming per portion. Pre-packaged

corpora will generally include metatextual information about individual texts

and their sources, and categorizations of their contents. They may also

incorporate details of text structure, annotation of part-of-speech or

syntactic features, etc.

·

Designer

software. Many

off-the-shelf corpora come with specially-designed interrogation software, such

as the SARA interface, which was designed to allow the BNC’s metatextual

documentation to be exploited in interrogating the corpus. All-purpose, plain

text concordancers such as Wordsmith Tools (Scott 1999) or MonoConc

(Barlow 1998) cannot generally interpret such information satisfactorily.

·

Convenience.

It is clearly less

effort to use a pre-packaged corpus than to make your own. All you have to do,

as it were, is open the tin. Most readers of this paper will have their own

favourite corpora, and many will feel that using them is vastly preferable to

going through the effort of designing and constructing their own. This is

perhaps the main factor to justify the compromise strategy to be outlined in

the next section.

3. The

pick’n’mix compromise

One way to avoid much of the effort

involved in constructing your own corpus (or fruit salad) is to steal the

necessary ingredients from elsewhere. The web is one prolific source of corpus

ingredients (Bertaccini & Aston 2001), but these may require complex

searches and considerable adaptation before they can be used (Pearson 2000). A

more attractive strategy may be to extract a subcorpus from a larger corpus,

whose texts can be treated as pre-prepared ingredients, just waiting to be

selected in the desired proportions. The analogy here might be with a (fruit)

salad bar, where you put together your own mixture from a series of bowls, each

containing one kind of fruit which is ready washed, peeled and chopped into pieces

of the right size. Here you can control the ingredients, selecting those which

appeal to you. You can decide for a preponderance of raspberries, or indeed

select or avoid one particularly bloated raspberry. You can omit the grapefruit

or add another dollop of cream. The following conversational extract

illustrates the process fairly well (however dubious you may be as to the

result):

PS0A2: Right there’s erm (.) it’s a tin of

fruit salad but I’ve put in some er kiwi and grapes (.) so it’s fresh fruit,

it’s in its own juice, so it’s not in a heavy thick juice, there’s Vienetta or

you can have a bit of each

PS09U: Well I’ll have a little bit of each

then please

(BNC Sampler:

KC2)

As well as an increase

in control, the fruit salad bar provides an increase in certainty (you have a

clearer idea what went in), and also in opportunity for creativity and

communication. Repeated attempts may also lead to increased critical awareness.

The fruit salad bar is convenient, requiring little effort bar that of decision-making.

Substantial reliability can be maintained (assuming the components are subject

to quality control), allowing you to draw on the documentation provided for

each component, and to exploit it in designing and consuming your own mixture.

In the same way, if you construct your own subcorpus

from the ingredients provided by a larger corpus, you can (within the limits of

what is on offer) choose your own text-types, and indeed individual texts. Not

only can you thereby increase control over and certainty as to the content, but

you can also indulge your creativity, and exploit opportunities to communicate

about your strategies and their results. In the process you may – through trial

and error – become more critically aware of what are (and are not) useful

subcorpora, and what are (and are not) appropriate design criteria. As we shall

see in the next section, constructing your own subcorpora in this manner can

maintain much of the reliability and conserve the documentation attached to the

original corpus, as well as allowing you to exploit software specifically

designed for use with that corpus. It is also far less work than compiling a

corpus of your own.

4. The

SARA subcorpus option

Recent releases of the BNC Sampler

(1999) and the just-published BNC World edition (2001) come with enhanced

software (SARA98) which allows users to define and then analyse subcorpora

within the corpus in question. Since SARA can be used with any TEI-conformant

corpus, the procedures outlined below are not, in theory, limited to the BNC,

but can also be applied to other corpora which adopt similar encoding

principles.

The

SARA subcorpus option allows the user to define subcorpora consisting of:

·

one or

more specific texts selected from a list of all the texts in the corpus;

·

all

those texts which contain solutions to a particular query, for instance all

those containing the word “Austria”.

Since SARA permits queries

concerning the metatextual information provided with the texts as well as

regarding their linguistic content, this second procedure can also be used to

define subcorpora consisting of all the texts belonging to a particular design

category (spoken/written, monologue/dialogue, imaginative/informative, etc.),

or to a particular descriptive one (e.g. produced by a particular type of

author/for a particular type of audience, or belonging to a particular genre:

cf. 4.4 below and Lee, this volume). The two procedures can also be combined,

with manual editing of the list of texts obtained from a particular query.

Once

defined, a subcorpus can be saved and used as the basis for subsequent queries.

It is also possible to index a saved subcorpus for easy re-use in subsequent

sessions. In the rest of this paper I illustrate some practical examples of

indexed subcorpora extracted from the BNC Sampler, and relate these examples to

the learner uses of corpora described earlier (cf. 2 above).

4.1 A

specific text as subcorpus

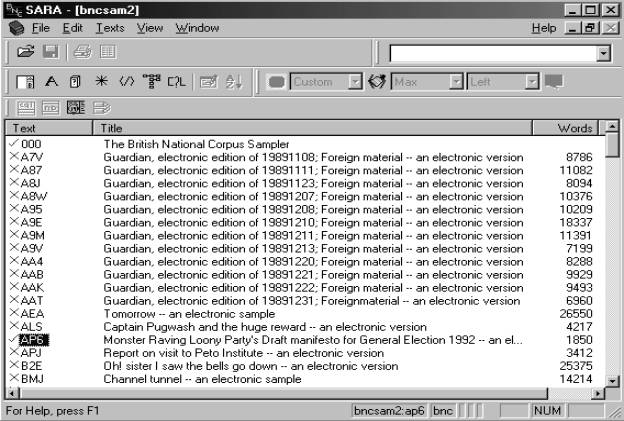

Scrolling through the list of texts

in the BNC Sampler, I was struck to discover the Monster Raving Loony Party’s

Draft manifesto for the British General Election of 1992 (AP6: Figure 1). Given

the resurgence of extremist political parties in Europe today, I felt that

participants at this conference, like many learners, might share my curiosity

concerning this text:

Figure 1. Selecting texts for inclusion in the

subcorpus

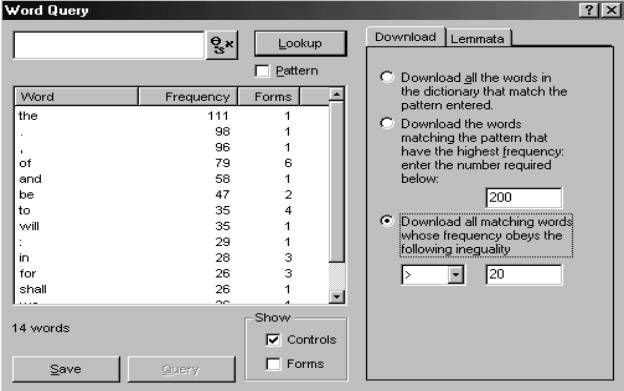

If we select this text and save it

as a subcorpus, we can then begin to pose queries about it. In the first place,

we can simply ask for a list of the most common words in it, shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2. Words whose frequency in the

subcorpus is greater than 20

One striking feature here is the

high frequency of the modals will and shall. This is presumably

because manifestos announce programmes, providing declarations of intent as to

future action. This is confirmed when we look at the results of a query for

these two forms (followed by be + past participle: Figure 3):

Figure 3. Shall/will be VVN in

the Monster Loony Party Manifesto

While the distribution of shall

and will in these citations is not easy to account for, the concordance

clearly demonstrates how a subcorpus consisting of just one text can highlight

its distinctive formal characteristics, and also cast light on its style and

meanings – as well as providing ample opportunity for discussion.

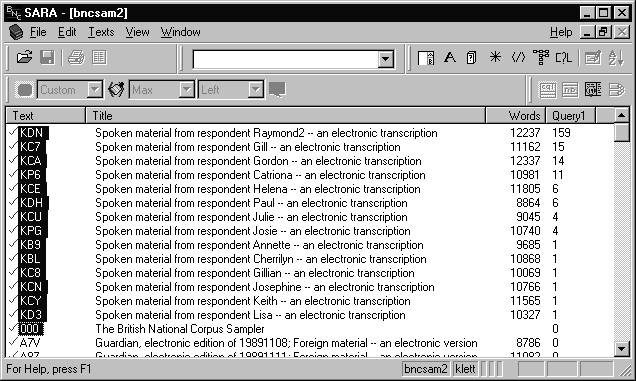

4.2

A bad language subcorpus

Subcorpora need not, of course, be

limited to a single text. If we carry out a query in the spoken texts of the

BNC Sampler for forms beginning with the characters fuck, we find 225

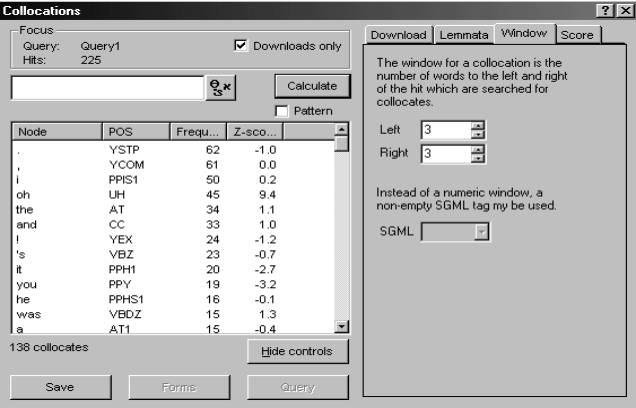

occurrences in 14 texts. In Figure 4, these texts are listed in order of the

number of occurrences found (see the Query 1 column), so we can easily

select all those which contain these forms as a subcorpus:

Figure 4. Texts containing forms of fuck[1]

In a browsing activity,

this subcorpus could be employed to explore various aspects of bad language

use. For example, we can generate a list of the collocates of the forms in

question to cast light on their typical usage within these texts (Figure 5).

What emerges most strikingly here is the collocate oh, which occurs no

less than 45 times in a span of 3 words to the left and to the right. As a

curiosity, it then comes naturally to ask what other words (if any) oh

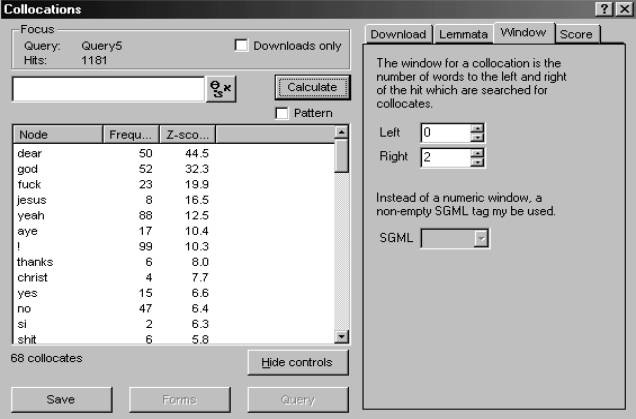

precedes in this subcorpus (Figure 6):

Figure 5. Collocates of forms of fuck

in the bad language subcorpus, distinguished by part-of-speech and ranked by

frequency

Figure 6. Right collocates of oh in

the bad language subcorpus, ranked by z-score

Ranking the collocates in a span of

2 words to the right of oh in order of significance (Figure 6), we

obtain a list which suggests that we have indeed created a subcorpus of bad

language texts, including a number of other expressions with oh which

learners wishing to improve their abusive competence might explore to their

profit. It might also be of interest to compare the usage of male and female

speakers – is it women or men who say oh

dear? This is another area which can be investigated thanks to the metatextual

information provided in the corpus and the specialized design of the

interrogation software.

Clearly, the number of

texts included in this subcorpus is very small, and we cannot assume that they

constitute a reasonable cross-section of spoken texts involving bad language.

Nonetheless they may still enable the user to generate, if not to definitively

test, hypotheses as to use in this area. The other subcorpora discussed in the

next sections are similarly too small to permit definitive conclusions, but

they can again provide interesting suggestions as to language use in certain

kinds of contexts.

4.3 Subcorpora

of encoded categories of texts

The spoken texts in the BNC fall

into two main classes, demographic and context-governed. These labels, which

refer to the way in which recordings were collected, distinguish free

conversations from talk recorded in settings of an institutional nature –

classrooms, courtrooms, business meetings, and the like. The context-governed

texts may be either monologue or dialogue – a feature which is again indicated

in the BNC text classification. A search for context-governed monologue in the

BNC Sampler finds 17 texts, while a search for context-governed dialogue finds

29. We can use the same procedure as in the last section to list the texts

which match these queries, and to form separate subcorpora of context-governed

monologue and dialogue texts.

Analysing

these two subcorpora, we find considerable differences. If we compare the 200

most frequent words in each, we find that could, had, he, know, their, were,

when, who, and your are ranked more than 20 positions higher in the

monologue subcorpus, while ’ll, ’m, any, no, pounds, right, yeah and

yes are more than 20 positions higher in the dialogue subcorpus. The differences

in the frequencies of yeah, yes, no and right suggest that

speakers may be less concerned with explicitly negotiating agreement when they

hold a monopoly of the floor (for instance, we find that there are no

occurrences of all right in the monologue subcorpus). There also appears

to be a difference in the use of pronouns: for instance, we find that we is

relatively more frequent in dialogue, and you in monologue (Figure 7):

|

|

we |

you |

|

Monologue |

2014 |

4253 |

|

Dialogue |

4949 |

6635 |

Figure 7. Occurrences of we and you in the monologue and dialogue

subcorpora

Perhaps this is again due to the

unwillingness of speakers in monologue contexts to claim shared attitudes with

their audiences, given that the latter have little chance to disagree. By

examining sample sets of citations, it may however be possible to advance other

hypotheses to account for these differences, and in any case for learners to

reflect on the linguistic differences between monologue and dialogue settings.

4.4 Subcorpora

based on other categorizations

It is also possible to define

subcorpora which are based on different categorizations from those originally

encoded by the corpus designers. Lee (this volume) provides a personal

categorization of the written texts in the BNC, based on criteria such as

academic vs non-academic, prose vs poetry, fiction vs non-fiction.[2]

We can use Lee’s lists to define subcorpora from the Sampler corresponding to

such categories as:

·

academic

non-fiction (13 texts);

·

non-academic

non-fiction (15 texts);

·

prose

fiction (13 texts).

Looking at wordlists for

these three subcorpora, we discover a number of items which appear to be more

common in one than in the other two. For example, the following adverbs in -ly

all occur more than 15 times in the subcorpus indicated, and less than 10 times

in each of the others:

academic non-fiction: accordingly, essentially, eventually, largely, namely, notably, respectively, surprisingly

;

non-academic non-fiction: effectively, merely, normally, obviously, possibly, specially

;

·

prose fiction: carefully, quietly, slightly,

slowly, softly, surely, truly.

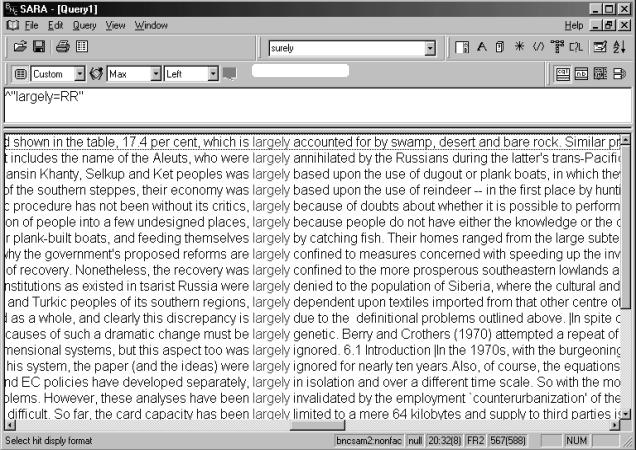

If we take just one of the items from the academic non-fiction list, largely, we can follow the traditional procedures of data-driven inductive learning to explore its uses in this genre (Johns 1991). On the one hand, largely appears to qualify participial predicates with a negative semantic prosody, collocating with

expressions like annihilated by, confined to, denied to,

ignored, invalidated by and limited to. On the other hand, it appears

to qualify linking expressions introducing causes, such as accounted for,

based upon, because, dependent upon and due to (Figure 8):

Figure 8. Largely in academic

non-fiction (Lee’s categorization)

There are two apparent exceptions to

these patterns in this concordance – largely by catching fish and largely

genetic – which I leave to the reader to account for.

A concordance of this

kind casts light on the language of the text-type in question by providing a

limited, relatively homogeneous set of citations, which are easier to

categorize and interpret than ones taken from a broader variety of texts. While

in no way permitting an exhaustive account of the ways in which the word largely

can be used, the concordance clearly illustrates two uses which would seem

to play a significant role in this text-type, and which may therefore be of use

to those who are learning to deal with such texts in their reading or writing.

A subcorpus of this kind

could also be used in other ways: to generate exercises in reading academic

prose (for instance in parsing nominal groups containing particular heads:

Brodine 2001), or as reference tools to assist learners with other features of

academic writing. Taking instead a browsing perspective, investigating largely

may lead the learner to examine near-synonyms (mostly, mainly, to a large

extent, for the most part), or to examine other collocates of such

expressions as confined to and limited to.

Nor

need the learner’s investigations be confined to this subcorpus alone. We have

seen that largely appears particularly frequent in texts classed as

written academic prose, but in analysing its uses in those texts, we have not

posed the question of whether it has the same uses in other text types. The

entry for largely in the Collins Cobuild dictionary (1995) suggests that

this may not be the case, since it cites examples from the Bank of English

which fit into neither the causative or the negative prosody category: The

fund is largely financed through government borrowing … I largely work with

people who already are motivated … Their weapons have been largely stones.

Working with a subcorpus frequently invites comparison of the results obtained with those from other

subcorpora, or indeed from the whole corpus from which the subcorpus has been

derived. Starting from a limited set of texts of a single type will simplify

this process insofar as it reduces the initial number and variability of

citations – providing, that is, a line of approach to the analysis of samples drawn

from the full corpus (Gavioli 2001).

5. Conclusions

Through these examples I hope to

have illustrated how subcorpora derived from the BNC Sampler can allow learners

to carry out activities of each of the types listed in 2 above, in particular:

·

to study and compare forms in particular texts or

text-types, contrasting these with those in other texts or text-types;

·

to study and compare meanings in particular texts or

text-types, contrasting these with those in other texts or text-types;

·

to carry out focussed reading practice;

·

to adopt appropriate reference tools for particular

tasks;

·

to carry out focussed browsing.

At

the same time, I would argue, subcorpora like these share many of the

characteristics which have motivated proposals to use ‘home-made’ corpora in

language learning (cf. 1 above). To summarize:

·

Subcorpora

can provide small, manageable amounts of data of a more homogeneous nature than

is possible with large mixed corpora, thereby facilitating analysis. It is, of

course, essential for users to recognize that such subcorpora are neither

sufficiently large, nor sufficiently carefully designed, to be considered

“representative” samples of the text-types involved, and that inferences made

from them should not be treated as definitive. However, as I have stressed

elsewhere, language learning appears to be a matter of progressive

approximation on the basis of ever-growing experience (Aston 1997). Thus, while

a learner who sees the two uses of largely presented in 4.4 above cannot

pretend to have fully understood all the potential uses of the word in academic

discourse, s/he arguably has formed an idea of two of the main ways in which it

can be used, and is well placed to refine this knowledge further in the future.

·

Subcorpora can provide a specialized environment for

the study of particular texts and instances. As the subcorpora described in

this paper were all taken from the BNC Sampler (which contains a mere 2% of the

texts in the full BNC), they were extremely small, and also relatively unspecialized.

With the new BNC World edition, however, more highly specialized subcorpora can

be constructed – not just of written academic discourse, but of written

academic discourse in the field of medicine, not just of spoken monologue but

of lectures, and so on.

Increased specialization entails increased homogeneity, and consequently more

precise focussing and reduced dispersiveness in corpus use. Alternatively, much

larger subcorpora can be extracted for categories like those discussed in the

last section, with a corresponding increase in reliability: there are, for

instance, 504 texts classed as written academic prose in the World edition,

which include 2348 occurrences of largely. These larger numbers may

however be difficult for learners to manage, initially requiring analyses of

smaller selections. Consequently there would still seem to be a pedagogic place

for small subcorpora such as those illustrated here, as points of initial focus

for the learner to generate hypotheses which can then be tested against the

larger subcorpora obtainable from the full BNC. Nor should we forget that the complete corpus, with its myriad

paths for the motivated learner to adventure down, is always there to be

consulted (Bernardini 2000).

·

If

learners create and select their own subcorpora for particular tasks, they will

also acquire practice and experience in corpus design which may be of use to

evaluate corpora with which they are unfamiliar, or to create corpora of their

own from less structured sources, such as the Web. These skills would appear

useful not only for would-be readers, writers and translators of specialized

texts, but also for more general-purpose language learners, insofar as the

latter need to develop a sensitivity to genre and register variation. It is

clear that subcorpora extracted from large mixed corpora like the BNC cannot be

expected to satisfy all possible requirements – only a specifically collected corpus of

astrophysics is likely to provide enough information concerning white dwarfs or

the rhetoric of astronomers; only a corpus of learner texts will satisfy the

need to study learner or lingua franca English (Granger 1998, this

volume; Seidlhofer 2000). But, one might argue, it is precisely because

subcorpora have these limits that they can provide valuable ways of learning to

design and use corpora in general.

References

Aston, Guy (1997), “Small and large

corpora in language learning,” in: Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk/Melia (1997), 51-62.

Aston, Guy (2000), “The British

National Corpus as a language learning resource,” in: Battaner/Lopez (2000),

15-40.

Aston, Guy, ed. (2001a), Learning

with corpora, Houston TX: Athelstan.

Aston, Guy (2001b), “Learning with

corpora: an overview”, in: Aston (2001a), 7-45.

Barlow, Michael (1998), MonoConc,

Houston TX: Athelstan.

Battaner, M. Paz/Carmen López, eds.

(2000), VI jornada de corpus linguistics, Barcelona: Institut

universitari de lingüística aplicada, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Bernardini, Silvia (2000a), Competence,

capacity, corpora, Bologna: CLUEB.

Bernardini, Silvia (2000b),

“Systematizing serendipity: proposals for concordancing large corpora with

learners,” in: Burnard/McEnery (2000), 225-234.

Bernardini, Silvia/Federico

Zanettin, eds. (2000), I corpora nella didattica delle lingue. Bologna:

CLUEB.

Bertaccini, Franco/Guy Aston (2001),

“Going to the Clochemerle: exploring cultural connotations through ad hoc

corpora,” in: Aston (2001a), 198-219.

Biber, Doug (1993),

“Representativeness in corpus design,” Literary and linguistic computing

8, 243-257.

Bowker, Lynne (1998), “Using

specialized monolingual native-language corpora as a translation resource: a

pilot study,” Meta 43, 631-651.

The British National Corpus World

Edition (2001),

Oxford: Oxford University Computing Services.

The BNC Sampler (1998), Oxford: Oxford University

Computing Services.

Brodine, Ruey (2001), “Integrating

corpus work into an academic reading course,” in: Aston (2001a), 138-176.

Burnard, Lou/Tony McEnery, eds

(2000), Rethinking language pedagogy from a corpus perspective, Frankfurt

am Main: Peter Lang.

Collins Cobuild Dictionary (1995, 2nd edition), London:

HarperCollins.

Gavioli, Laura (1997), “Exploring

texts through the concordancer: guiding the learner,” in:

Wichmann/Fligelstone/McEnery/Knowles (1997), 83-99.

Gavioli, Laura (2001), “The learner

as researcher: introducing corpus concordancing in the classroom,” in: Aston

(2001a), 108-137.

Granger, Sylviane, ed. (1998), Learner

English on computer, London: Longman.

Johns, Tim (1991), “Should you be

persuaded: two samples of data-driven learning materials,” English language

research journal 4, 1-16.

Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk,

Barbara/James Melia, eds. (1997), Palc ’97: Practical applications in

language corpora, Łódz: Łódz University Press.

Maia, Belinda (2000a). “Making

corpora: a learning process,” in: Bernardini/Zanettin (2000), 47-60.

Maia, Belinda (2000b), “Comparable

and parallel corpora – and their relationship to terminology work and

training”, Paper presented at 2nd Corpus Use and Learning to Translate

conference, Bertinoro.

Owen, Charles (1996), “Do corpora

require to be consulted?” ELT journal 50, 219-224.

Pearson, Jennifer (1998), Terms

in context, Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Pearson, Jennifer (2000), “Surfing

the internet: teaching students to choose their texts wisely,” in:

Burnard/McEnery (2000), 235-239.

Raffa, Giuliana (2000), The

astrophysics research article: a corpus-based analysis. Unpublished

dissertation. Forlì: SSLMIT.

Scott, Mike (1999), Wordsmith

tools ver. 3.0, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seidlhofer, Barbara (2000),

“Operationalizing intertextuality: using learner corpora for learning,” in:

Burnard/McEnery (2000), 207-223.

Sinclair, John (1991), Corpus

concordance collocation, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Varantola, Krista (2000),

“Translators and disposable corpora”, Paper presented at 2nd Corpus Use and

Learning to Translate conference, Bertinoro.

Wichmann, Ann/Steve Fligelstone/Tony

McEnery/Gerry Knowles, eds. (1997), Teaching and language corpora,

London: Longman.

Willis, Dave (1998), “Learners as

researchers,” Paper presented at IATEFL 32nd annual conference, UMIST,

Manchester.

Zanettin, Federico (2001), “Swimming

in words: corpora, translation, and language learning,” in: Aston (2001a),

177-198.